Are Kurds “Worthy Victims” in the Eyes of the Media?

International media talked about Kurdish issues when Islamic State or Donald Trump were involved, the data shows. Otherwise, Kurdistan was out of sight and out of mind.

Complaining about journalists — that they are ignoring or deflecting from an important issue — is a universal pastime. And it’s an especially sensitive issue for minorities and stateless peoples struggling for recognition, for whom outside sympathy is often a matter of life and death.

These complaints are often grounded in reality. In his famous media study Manufacturing Consent, linguist Noam Chomsky argued that the American press treats different people around the world as “worthy” or “unworthy” of sympathy depending on their relationship to U.S. politics.

Chomsky cited the Kurdish question in the introduction to the book’s 2002 edition. American media was far more sympathetic to Kurds oppressed by Iraq than by Turkey, he claimed, because Turkey was a U.S. ally while Iraq was an official enemy. The documentary Good Kurds, Bad Kurds, published in 2000, made the same point.

And even the sympathy for Iraqi Kurds is a recent phenomenon; in the 1980s, when Iraq was a U.S. partner, the U.S. government helped cover up Iraqi atrocities against Kurds.

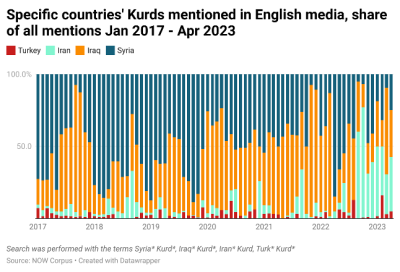

Two decades later, U.S. relationships with Iraq, Turkey, and various Kurdish movements have shifted. But the fundamental points that Chomsky made are still relevant. English-language media focuses on Kurdish issues when they are relevant to American politics. The press still tends to ignore politically inconvenient victims, such as those who are oppressed by U.S. allies. This effect even seems to apply to non-American publications that write in English.

The choice of which story to tell has real effects on people’s lives. Government “villainy may be constrained by intense publicity,” as Chomsky argues. Most states fear foreign pressure and try to keep their “internal affairs” out of the spotlight. International coverage of an issue forces local media to address that issue, even when censors would prefer to bury the story.

A look at the data shows which Kurdish issues are an object of international attention, and which ones are “out of sight, out of mind” for journalists. The data on media coverage comes from the News on the Web (NOW) Corpus, a database of English-language publications from twenty-one countries. The data on violence comes from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) monitor, which has recorded incidents of violence in various countries over the past few years.

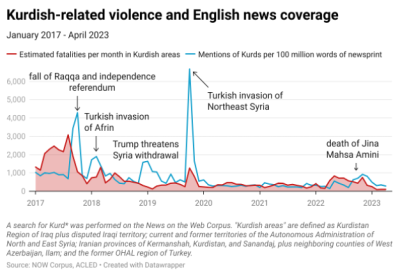

The war in Syria — and the events surrounding it, such as the Islamic State rebellion in Iraq and the Iraqi Kurdish independence referendum — drove much of the foreign coverage of Kurdish issues. That makes sense. The Islamic State was an international threat, and the Syrian civil war was the most violent of all conflicts Kurds were involved in at the time.

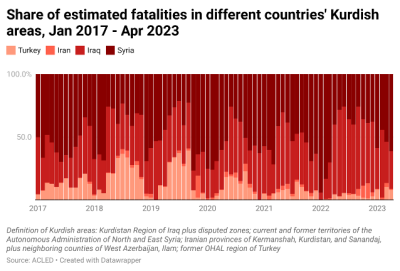

Phrases like “Syrian Kurds” and “Iraqi Kurdistan” were the most common country-specific phrases in international media. Not only were Kurdish areas in Syria and Iraq the scene of the most intense violence, but Iraqi Kurdistan is also a region with official status, while “Syrian Kurds” is a common shorthand for the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria.

Turkey’s Kurds were mentioned very little for the share of the violence they endured. The omission is especially glaring because much of the recent violence in Syria and Iraq has been driven by the Turkish-Kurdish conflict.

The single largest burst of coverage came in October 2019, when U.S. President Donald Trump green-lit a Turkish invasion of Syria as part of a plan to withdraw U.S. forces from the country. That coverage died down when Turkey agreed to halt its invasion in mid-October, even though Turkey continued to occupy parts of Syria and threaten further incursions.

Surprisingly, the fall of the last Islamic State holdouts in March 2019 did not drive much coverage of the Kurdish forces involved. The Battle of Raqqa in 2017 seems to have been the end of the Islamic State as an important story in its own right. Afterwards, much of the American coverage focused on debunking or mocking Trump’s claims about the war rather than the war itself.

“The political polarization of American life after 2016 saw viewers drift away from whatever interest they showed in confusing wars in far-off places for an obsession with their own internal conflict,” former VICE producer Aris Roussinos recently observed. “The rest of the world retreated back into obscurity — unless it could be viewed through Trump’s prism.”

Mentions of Iranian Kurds picked up during the recent uprising in Iran, which has received vocal support in American political circles. That does not mean that the media was covering Iranian Kurdish affairs closely, however. Many articles simply included a sentence mentioning that the uprising was kicked off by the death of Kurdish woman Jina Mahsa Amini in police custody, without following up on the intense repression Kurdish areas have faced since then.

Of course, Iranian Kurdistan and Iran as a whole are almost impossible for journalists to access. Niloofar Hamedi and Elaheh Mohammadi, the Iranian photojournalists who broke the story of Amini’s death, have been jailed as spies. Given the intense repression, foreign media has had to rely on social media or diaspora networks for information coming out of Iran.

In addition to outright threats and censorship, there are several “filters” that allow elites to restrict and manipulate journalists, Chomsky theorizes.

Reporting is expensive work. News organizations tend to be owned by wealthy business interests. In order to turn a profit, media outlets have to supplement their subscriptions with advertising revenue. And in the eyes of advertisers, the best content appeals to a wealthy consumer base.

The journalists themselves must cozy up to powerful institutions for access to information. Those institutions can retaliate for negative coverage by creating legal annoyances or stirring up public anger, a process Chomsky calls “flak.”

Several of those filters shape coverage of Kurdish issues. Kurdistan is more difficult and costly for journalists to visit, even compared to other conflict zones. While Ukraine is well-connected to Europe by railroad, and Israel and the Palestinian territories are a small urbanized space, the Kurdish homeland is vast, mountainous, and largely rural. It is also split between four states with several official and unofficial languages, which adds another layer of complexity.

Access comes with political tradeoffs, too. Many international outlets cover Iran and Syria from their Istanbul bureaus. Iraqi Kurdistan hosts much of the Iranian Kurdish opposition, and the only border crossing with Northeast Syria, which the Iraqi Kurdish government often restricts access to. Pushing too hard in a direction that Turkish or Iraqi Kurdish authorities do not like makes it substantially harder to tell Iranian and Syrian stories.

A report on Kurdish political prisoners may cost more than the advertising revenues it brings in, on top of all the headache and opportunity costs. A feel-good story about Kurds fighting alongside Western militaries is much more likely to turn a profit and open future doors.

Journalists themselves prefer stories that place their own country on the “right” side of history. That is the final filter, which Chomsky first identified as “anticommunism” and later called “the Common Enemy.” As much as the media is willing to air domestic criticism, it likes to remind viewers that foreign enemies are the real villains.

Chomsky used the killing of religious dissidents in Eastern Europe and Latin America as a case study. When the Polish secret police murdered Father Jerzy Popiełuszko, intense international scrutiny fell on Poland’s Communist government, which ended up arresting and prosecuting intelligence operatives over the priest’s death.

At the same time, anticommunists were carrying out brutal repression across Latin America with U.S. backing. Mainstream American media rarely paid attention to the individual victims and did little to follow up on their stories. Chomsky noted that Popiełuszko’s assassination received more coverage than the slaughter of a hundred religious dissidents in Latin America put together.

In other words, Chomsky wrote, “a priest murdered in Latin America is worth less than a hundredth of a priest murdered in Poland.”

Today, those persecuted by NATO ally Turkey receive less attention than those persecuted by official enemies. Compare the cases of Selahattin Demirtas, leader of the largest Kurdish party in Turkey, and Alexi Navalny, the most prominent Russian opposition politician. Both were arrested on trumped-up charges, given unfair trials, and sentenced to long prison terms. Both have been accused of terrorism based on vague associations and their political speech.

English-language media has mentioned Navalny about 1,285 times per billion words since his January 2021 arrest. By contrast, the same outlets have mentioned Demirtaş only about 39 times per billion words of newsprint since his November 2016 arrest. Of course, Russia is a larger state than Turkey, so more people are affected by Russian repression, but not by a factor of thirty.

And not all attention is created equal. Journalists must always decide which details to mention, which sources to quote, and which questions to ask when reporting a given story. These choices influence how much sympathy audiences give to victims and whom they blame for injustice.

The Popiełuszko case showed that journalists were capable of drawing attention to the gruesome details of repression while humanizing its victims. The American press did not extend the same treatment to religious dissidents in El Salvador, such as Archbishop Óscar Romero and the Maryknoll nuns, many of whom were killed under very disturbing circumstances.

“While the coverage of the worthy victim was generous with gory details and quoted expressions of outrage and demands for justice, the coverage of the unworthy victims was low-keyed, designed to keep the lid on emotions and evoking regretful and philosophical generalities on the omnipresence of violence and the inherent tragedy of human life,” Chomsky wrote.

In that regard, the media sometimes treats Kurds repressed by Turkey as worthy victims. The New York Times and Washington Post have both helped Demirtas speak out from behind bars. The torture and execution of Syrian Kurdish politician Hevrin Khalaf by Turkish-backed paramilitaries in October 2019 provoked worldwide outrage. Many outlets compassionately covered the story of Khalaf’s life and the meaning of her political work.

Elsewhere in the region, Kurds from Iraq, Iran, and Syria have been the subject of humanizing coverage in mainstream international media.

However, the media has not consistently followed up on these stories. The same Turkish-backed militias that killed Khalaf have continued to terrorize civilians, especially women and minorities like Yezidis, in the occupied territories. And Turkish drones have assassinated many other Syrian political figures since the 2019 invasion. Those victims have not received personalized coverage about their plight, and many of the incidents have gone completely unreported outside of local press.

Khalaf’s murder came during a dramatic break in U.S.-Turkish relations, one tied to domestic American politics. Trump had sided with Turkey against the wishes of Congress and the U.S. military, and there was political space to draw attention to the horrifying consequences. Today, Turkey’s actions in Syria are seen as “business as usual.” Even U.S. policymakers who oppose the situation prefer to keep their dispute with a NATO ally behind closed doors.

Of course, becoming an object of debate in American politics does not always lead to sympathetic or humanizing coverage. For example, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is one of the most heavily-covered issues in international media, especially American media. In that coverage, Palestinians often play the role of side characters or antagonists in American or Israeli stories.

“U.S. media talks a lot about Palestinians — just without Palestinians,” the Palestinian-American scholar Maha Nasser wrote in 2020.

Nasser found that the New York Times ran 2,490 opinion pieces about Palestinians over the previous five decades, and only 46 of those articles had a Palestinian author. The ratio improved over time, just barely. From 2010 to 2019, the New York Times ran 644 opinion pieces about Palestinians, eighteen of them with a Palestinian author.

“Instead [of hearing Palestinian perspectives], readers’ views were shaped by columnists whose copious opinion pieces about Palestinians ranged from the annoyingly condescending to the outright racist,” Nasser noted.

Similarly, most New York Times opinion articles about Kurds from 2010 to 2019 were written by non-Kurdish authors. The paper published 93 opinion columns and op-eds about Kurds in that time frame, only 17 of them with Kurdish authors. (The ethnicity of eight other authors is unclear.)

Although many non-Kurdish writers were sympathetic to the Kurdish cause in general terms, some were loudly and proudly ignorant about the actual issues at stake.

“If you think there is a simple answer to this problem, you ought to come out here for a week,” star columnist Thomas Friedman surmised during a trip to Iraqi Kurdistan in March 2016. “Just trying to figure out the differences among the Kurdish parties and militias in Syria and Iraq — the Y.P.G., P.Y.D., P.U.K., K.D.P. and P.K.K. — took me a day.”

That was during a period of exceptional American interest in Kurdish issues. From 2020 to 2023, Kurdish issues all but dropped from the New York Times opinion section. Ironically, the loss of interest allowed local voices to lead the conversation. The few op-eds about the Kurdish question since 2020 were written by Cihan Tugal, a Turkish-American academic sympathetic to the Kurdish cause, and Garo Paylan, a lawmaker of Armenian origin in Demirtaş’s party.

A few non-Kurdish authors mentioned Kurds in passing, including columnist Roger Cohen, who wrote in October 2020 that “the Palestinians have overtaken the Kurds as the most tired cause in the Middle East, some achievement.”

Nasser believes that Palestinians “are not waiting for the legacy outlets to catch up with the times.” Alternative news outlets and social media now allow them to reach global audiences more directly. As a result, both ordinary people and decision-makers “wanting Palestinian perspectives now have a much easier time getting them,” Nasser wrote.

Other stateless peoples also benefit from these changes. Kurdish movements have taken full advantage of the Internet to get their point across. Iraqi Kurdish stations like Rudaw and Kurdistan24 now publish content online in multiple languages. The Rojava Information Center (RIC) in Syria and the Hengaw Organization for Human Rights in Iran provide on-the-ground updates directly via social media.

Legacy outlets still play a role, because they have an audience and prestige that alternative media cannot hope to match. For better or for worse, outside journalists are considered to be more “impartial” sources than local activist media.

The flourishing of alternative and social media also pushes those legacy outlets to improve their coverage. RIC and Hengaw have become trusted sources for foreign journalists, thanks to a successful outreach strategy. And “flak” is no longer a tactic reserved for the powerful. Social media allows locals to directly call out inaccurate or insensitive coverage about their lives.

Kurds who wish to get their message to the world have an unprecedented opportunity to do so. They should understand the constraints they are operating under.

(Photo: U.S. Army photo/Sgt. 1st Class Jeremy Patterson)